Plaque Evaluation Course

FORD BREWER, MD MPH

Introduction

The Tragically Common Story About Plaque

April 29, 2008 was a beautiful day in Washington, DC. It was four weeks after the Cherry Blossom Festival. The weather outside was mostly sunny, with occasional clouds. The temperature was in the 50s most of the day, with a high of 62.

Dr. Michael Newman was a well-known internist. He was the doctor to Washington’s elite. One of those elite patients—a top figure in his field—was on the treadmill for a stress test.

Dr. Newman suggested that the patient lose weight. But that’s what docs do. Yes, this patient was getting older—now 58. Middle-aged men gain weight, but this had not negatively impacted this patient’s work. His job required lunch and dinner meetings with national and world leaders. He had to be totally focused. Who would want to be distracted with dieting when attending meetings?

He wasn’t ignoring Dr. Newman’s advice, though. He was trying, but it was hard. He knew what he had to do. He told the doc he was going to do it when the right time comes. And he meant it.

He and his doc both knew he had coronary artery disease. He got a positive calcium score several years ago. He had not had any chest pain. Dr. Newman pointed out that the best way to handle coronary artery disease was not with stents but with lifestyle and medications. The doctor adjusted his blood pressure medication, switching from an ACE inhibitor (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor) to an ARB (angiotensin II receptor blocker).

Others factors were favorable. His family history wasn’t ominous. He didn’t smoke. Even though they’d made adjustments in his medications, his blood pressure was controlled. Total cholesterol and LDL values were not high. Neither was his CRP (C-reactive protein), a measure of cardiovascular inflammation and potential risk for plaque rupture.

Dr. Newman was ahead of his time in using CRP for gauging heart attack risk. Even today, over 10 years later, a few doctors would attempt to measure cardiovascular (CV) inflammation. Nowadays, there are better ways to do this.

Dr. Newman also used the Framingham standards to estimate the CV risk of this patient. It was less than 10% for an event over the next 10 years. For a 58-year-old patient with coronary artery disease and a weight problem, you couldn’t ask for a better prognosis.

Passing the stress test was a relief. Obviously, this patient didn’t really believe he had a problem that needed immediate, drastic attention. As he’d told his doc many times, he did plan to deal with his weight when the right time comes. So he returned to work—and his life. And when his son, Luke, graduated from college, the family took a trip to celebrate the incredible achievement.

Still, he had to come home early to prepare for his upcoming show on June 15, Sunday. He came back on Friday the 13th, six weeks after he passed his stress test.

He collapsed while recording voice-overs. He died.

—

Andrea Mitchell, “Joining me now is a very close, close friend (pause) – a close friend of Tim Russert’s, who was with him, and – Dr Newman, you & I, we know each other, (pause) and both know Tim, but you had the sad duty of being with him today in the ER. I don’t know what you can share.”

Dr. Michael Newman, (exhales, then speaks). “It’s a, uh (another long pause), talk a bit about Tim, and talk a bit about cardiac disease, and sudden cardiac arrest. Tim had coronary artery disease. He had no symptoms, asymptomatic coronary disease as we see in many men and women. His risk factors were well-managed. He was well-informed. He did his best with respect to diet, exercise, lifestyle. His blood pressure was well-controlled. His cholesterol fractions were optimal. He had a stress test April 29th, got to a very high level of exercise. He was quite pleased with his performance as we were. This morning, as most mornings, he got on his treadmill and was always excited about how he pushed himself. Uh, these events, these sudden cardiac events, occur without warning. There is no way to anticipate or detect them. An hour before this happened, he could have had a stress test, and it would have been perfectly normal. The reason why these events occur is because you have rupture of cholesterol plaque in the wall of the coronary artery. And that causes a sudden cardiac, coronary thrombosis, which results to a heart attack, and the injury causes a fatal – in this instance – ventricular arrhythmia.”

Andrea Mitchell, “And this was a blood clot, when you say in the coronary…”

Dr. Newman, “A concern that we had was that perhaps this was related to a pulmonary embolus, because Tim had flown on Sunday to Rome for Luke’s birthday and graduation, and turned around. We did the autopsy to determine the cause of death. An autopsy is important despite all the technology and scans and imaging that we have. The autopsy showed that Tim had an enlarged heart and significant coronary artery disease in the left anterior descending coronary artery. And we could actually see fresh clot right in the coronary artery. That was the coronary thrombosis that triggered the coronary event and the arrhythmia from which he died.”

Andrea Mitchell, “Dr. Newman, help us with this, because we know him as such a vigorous, active man. He’d just flown back. He’d just taped a broadcast this morning, and was downstairs here, recording the opening sequence for MEET THE PRESS, and collapsed. Was there anything – the EMT guys got here very quickly. Is there anything they could have done? They worked on him for 10 minutes.”

Dr. Newman, “The, uh, as soon as we got the – a few moments it was recognized that Tim was in trouble. And one of the interns here, who’s a certified, uh, in CPR, along with some of the staff here, began CPR. And that was helpful. And a defibrillator is what makes the difference. In this sudden cardiac arrests, use of a defibrillator, – which they were in the process of doing – is important. The DC EMS arrived promptly, and they immediately defibrillated Tim. And they actually did it 3 times in transporting him to Sibley hospital.”

Andrea Mitchell, “Is there, in the brief time that we have left. Let me just clarify. This was a known condition?”

Dr. Newman, “He was known to have coronary artery disease. There are many men and women that have coronary artery disease. It was well-managed. There was a recent study, the COURAGE Trial, that showed that medical management of coronary artery disease is the way to go.”

Andrea Mitchell, “And, by the time he got, he was never resuscitated?”

Dr. Newman, “He was never resuscitated. The defibrillation efforts, the 3 of them, the full code, the epinephrine, simply did not work. Even in witnessed cardiac arrest, survival is about 5%.”

Andrea Mitchell, “And Tim Russert’s physical condition, his health, his weight – he exercised every day. I know he was coming here right from the treadmill.”

Dr. Newman, “His weight was an issue. His weight was an issue. Weight’s something that we all struggle with. Tim struggled with it. And he always said, ‘tomorrow! I’m going to start tomorrow, doc. I know what I have to do.’ ”

Andrea Mitchell, “Mike Newman, I know you as a friend of Tim’s. And I know how hard this is for you. And as his doctor, and how painful this is for everyone connected. And, we just want to thank you for sharing with our viewers, to be as open as possible about what happened here today. It was probably a comfort to people in this bureau to know that he was under your care. And he was working to manage his condition. So thank you.”

Dr. Newman, “It’s an extraordinary loss. And it’s something that, I’m certain, for all of us, we appreciate the uncertainty of our lives.”

Andrea Mitchell, “Never more so than tonight. There was no one better, larger, more heroic, more courageous in every aspect of his life – more loving to his family, to his friends, to his employees than my colleague, Timothy J. Russert.”

(From NBC News Special Report, June 13, 2008)

—

The office was that of WRC-TV, which housed the DC bureau of NBC News. Tim Russert was the bureau chief. According to NBC journalist Brian Williams, Russert’s last words were, “What’s happening?”, spoken in greeting to the editing supervisor Candace Harrington as he passed her in the hallway. He then walked down the hall to the soundproof booth.

As co-workers performed CPR, others called the DC Fire & Rescue who recorded receiving the call at 1:40 p.m. and dispatched an EMS unit. The unit arrived at 1:44 p.m. As mentioned by Dr. Newman in the transcript of the NBC News Special Report above, paramedics shocked his heart 3 times. They were trying to stop the chaotic ventricular fibrillation. But the attempts failed.

Russert was transported to Sibley Memorial Hospital. He arrived at 2:23 p.m. and was pronounced dead.

Dr. Newman mentioned about Russert’s long flight, raising the suspicion of a pulmonary embolus. Russert was coming home from a family trip to Rome. It was a celebration of his son Luke’s birthday and graduation from Boston College. His wife and son remained in Rome while Russert returned to prepare for his Sunday show.

Russert assumed the hosting job in 1991; he was the show’s longest-running host. He was passionate. His research was extensive. He often found quotes or video clips that were inconsistent with the current actions of high-profile government guests. A favorite line of him, “but those were your words, from … years ago…” Russert once quoted, “Our job is really that of watchdog… to hold our government accountable to its people.”

An inflamed, soft arterial plaque ruptured, ending Russert’s voiceovers, research, interviews, and career. It was a major loss, not only to Russert and his family but to the nation.

The New York Times incorrectly surmised that Russert’s doctors (and presumably Russert) didn’t even know that he had plaque. The doctor(s) “did not realize how severe the disease was because he did not have chest pain or other telltale symptoms that would have justified the kind of invasive tests needed to make a definitive diagnosis. In that sense, his case was sadly typical: more than 50 percent of all men who die of coronary heart disease have no previous symptoms, the American Heart Association says.” In an interview, Dr. Newman and Dr. George Bren (Russert’s cardiologist) said the autopsy found significant blockages in several coronary arteries (“A Search for Answers in Russert’s Death,” The New York Times, June 17, 2008).

The report that the doctors didn’t know Russert had plaque was incorrect. That’s presumably due to misinterpretation of Dr. Newman’s statements that Russert had “known coronary artery disease.” The NBC News Special Report transcript above shows that the doctors and Russert all knew that Russert indeed had plaque (coronary artery disease). Still, they were surprised by the extent of the plaque disease. And Russert had a positive calcium score (a sign of coronary heart disease) a decade earlier.

The following year, 2009, was the first year that screening of asymptomatic individuals was considered by the ACC (American College of Cardiology) and AHA (American Heart Association) Committee on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk.

Just what is plaque anyway? And why can’t we predict heart attacks?

Atherosclerosis—from the Greek roots athero meaning “artery,” and skleros meaning ‘hardening” or “scarring”—is responsible for the vast majority of heart attacks, strokes, blindness, and dementia.

Good thing, the process of atherosclerosis can be slowed down dramatically. In a society where preventive lifestyles are the norm, centenarians will become very common. In the past, we saw plaque as a result of normal aging. It has become clear that this isn’t the truth. In a new world with proper preventive lifestyles, screening, and treatment, 95 to 100 years is a more practical life expectancy.

In arteries, atherosclerosis is like acne. The usual assumption is that plaque is like hair clogging a bathtub drain. That notion is wrong. The description of Tim Russert’s arteries from the autopsy was that the inside looked like the skin of a pimple-faced teenager.

Why are heart attacks sudden and unexpected? Because, as in Russert’s case, we have chronic inflammation creating the pimples along the inside of our arteries. Inflammation is something that we can detect and measure. We’ll describe that later.

Perhaps you already experienced plaque growth, maybe even documented it with one of the methods described in this book. If so, you know that you just don’t feel plaque. Perhaps you’ve already survived an event. If so, you know that predicting such events using today’s standard medical treatments is impossible.

However, today’s medical treatments don’t involve measurement, plaque, or inflammation. Adding the practice of measuring plaque and inflammation should put us all in a whole new world of medicine. We can now move from a situation where we can’t predict (and presumably can’t prevent) majority of medical disasters, to a position where can now predict them. Theoretically, you can still prevent disasters without predicting. You just have to focus on strictly following preventive programs.

The keyword here, though, is “theoretically.” As a trained preventive medicine specialist (and supervisor/trainer of prevention for thousands of doctors), I used this nonspecific method for over three decades. I didn’t think all the testing made sense; they were too expensive. As a public health trainee and a man of faith, I had a passion for making good prevention available to the masses.

After my second retirement, I decided to experience “the dark side” of prevention, the space where the motto was “test, don’t guess.” The scientifically most rigorous of these was the Bale/Doneen world. Brad Bale and Amy Doneen wrote a book a few years ago titled “Beat the Heart Attack Gene.” This book was published in 2014.

The heart attack gene in the title is 9P21. That’s the P21 area of the 9th chromosome. The gene was originally linked with cancers then later found to be a heart attack gene. The underlying mechanism was found—9P21 is actually a gene that predisposes us to type 2 diabetes. And it’s very common: 3 out of 4 people have at least one copy of this gene.

There is a lot more to the 9P21 story, and there are many other stories behind the issue of genetics and cardiovascular disease. The purpose of this book, however, is to change our current practice in terms of plaque detection and measurement. We have to write a new and different book that will tell cardiogenetics stories.

Let’s get back to plaque and why heart attacks are sudden and unpredictable. Remember the pimples, the acne along the inside walls of the arteries described in Tim Russert’s autopsy? One of those pimples ruptured, spewing the contents into the blood. The inflammatory components of those contents can cause clot formation.

So, here’s what happened in Russert’s LAD (Left Anterior Descending) artery. By the way, LAD is known as “the widowmaker” as this is a common site for this kind of tragedy. (“Widowmaker” is also the name of a great movie created to spread awareness about the coronary calcium score screening tool. See Chapter 6: The Calcium Score.)

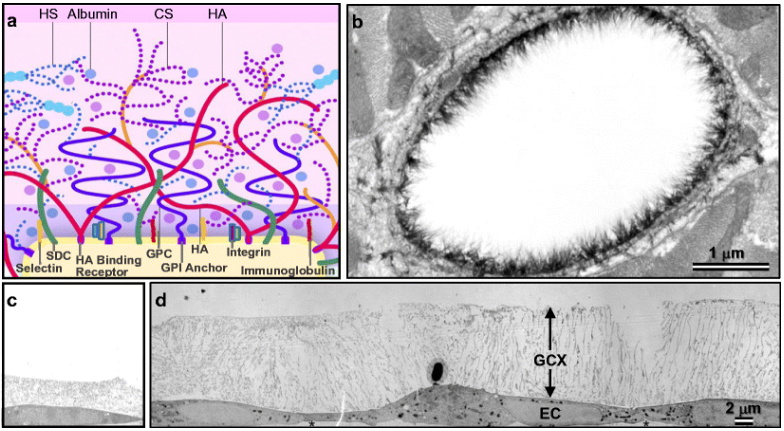

A deeper dive into the disease reveals chronic inflammation. In other words, it’s the work of our own immune system. When our immune system is at work, it destroys and removes plaque. The original injury appears to be damage to the glycocalyx, a component of the intima. The intima is the inner lining of the artery wall. The term IMT stands for “Intima Media Thickness.” The glycocalyx is like a brush sticking out into the flowing of the blood.

A better analogy here is that of a marsh. The glycocalyx is like the edge or intersection of a marsh and a river where the real biological action happens. It’s the same as the glycocalyx. It’s where nutrients and waste products are exchanged between cells and the bloodstream.

Figure A above is a representation of the glycocalyx, showing more its biological components. Figure B shows a larger picture, using a STORM method microscopy of an artery wall. Figure C shows an injured, thin glycocalyx. Figure D shows healthy, thicker glycocalyx.

Inflammatory agents (such as high blood sugar and smoking by-products) injure the glycocalyx. They could actually cut and thin the brush-like components (see Figure C above). When the glycocalyx is damaged, LDL (low-density lipoprotein) tends to slip through the intima layer and get lodged in the intima-media space.

It’s not entirely clear whether LDL is completely oxidized before it slips through the glycocalyx or oxidation happens after the LDL gets trapped in the artery wall. But one thing is sure: it’s mostly oxidized by the time it’s trapped. We can test for oxLDL (oxidized LDL) through blood samples. In fact, the major ACC/AHA standards for prevention and use of statins are determined by LDL levels.

That’s slowly changing as medical standards trail science. Evidence continues to show that LDL levels in the blood are not really as important as the damage to the glycocalyx. That certainly fits with my experience as a prevention doctor helping thousands of individuals each year with this problem.

Let’s look at FH (Familial Hypercholesterolemia). This is a genetic disorder resulting in LDL levels much higher than normal. FH is seen in about 1 in 200. It’s very much underdiagnosed. Most families with FH are not aware of their condition. That, too, is a big public health problem.

For the rest of us, typical “high” levels of LDL are considered to be 80-180. Once you get to LDL levels of 180, you should get the FH genetic test. It’s not so much for you; it’s for your family. FH patients often get LDL levels between 180 and 450.

Yet, even with these high levels, these patients usually have CV events when something else (like smoking, obesity, or prediabetes) is added to the mix. In other words, maybe it’s not just the LDL level alone. Maybe it’s the injury to the glycocalyx first. Then higher LDL levels just make the process quicker.

When oxLDL gets stuck in the intima-media space, it will attract immune cells. The immune system senses this inappropriate oxLDL deposit as an injury. Therefore, the immune system starts doing what it always does when something’s wrong: it creates inflammation.

Inflammation is simply the immune system’s approach to any damage. Once immune cells find their way to the location, they begin to release enzymes that destroy (liquify) the oxLDL. Other chemicals are released as well. Their role is to attract other immune cells to the inflammation area. These are called cytokines (cyto means “cell,” and kines means “attractants”).

There are several types of immune cells involved here, like monocytes, leukocytes, macrophages, and T lymphocytes. Things get more complicated: there are other types of cells, and these cells can sometimes morph into other types. To top it off, many of the cell types have more than one name, so don’t try to be too rigid in terms of understanding this process.

When monocytes are attracted, they penetrate the glycocalyx and intima layers, and get lodged in the intima-media space. Once activated, they change into macrophages. They “eat” oxLDL nonstop, growing into foam cells, and finally exploding. This stage of the process results in fatty streaks. Similar processes are involved in inflammatory stages of facial acne. That’s why the analogy with the lining of Russert’s arteries is so appropriate.

As the inflammatory process continues, there is a pooling of liquid materials consisting of immune cells, debris, cytokines, chemoattractants, and more. These “soft plaque” include bits of proteins, oxLDL, glycoproteins, etc. Several of these components are potent coagulants. One example is tissue factor, a glycoprotein, also called “factor X.” It’s an enzyme, part of the cytokine receptor class II. There are usually thin, fibrous caps over these liquid plaque pools. If the fibrous cap breaks, you get a plaque rupture. That’s what set off the sequence of events that killed Russert. It’s the most common killer and disabler of our species.

Speaking of CV inflammation, Dr. Newman did make some changes in Russert’s medications that may have impacted Russert’s CV inflammation process. He changed the ACE inhibitor (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor) to an ARB (angiotensin II receptor blockers). ACE inhibitors have demonstrated a calming impact on CV inflammation, especially together with statins. (By the way, I usually give statins for inflammation, not LDL.) ARBs are a similar type of medications, and they cause fewer side effects, like a cough. But the evidence is not that strong in showing that ARBs decrease CV Inflammation as well as ACE inhibitors.

Although Dr. Newman did not comment on this, that cough could have been the problem. Here’s why: the patient was Tim Russert. Many of us would debate on that medication change based on the position that ACE inhibitors are better at decreasing CV inflammation than ARBs. Still, a national television personality like Russert cannot afford to interrupt his broadcasts with repetitive coughing, and that may have been the reason for the switch from the more preventive ACE inhibitor to ARB.

Again, why are most CV events unpredictable. That’s because fibrous cap rupture of inflamed plaque cannot be predicted. Fortunately, we can now detect and measure inflammation through blood tests and simple artery scans (CIMT). Sadly, standard medical care does not include any of these processes. In this book, we will explain why.

THIS BOOK

The following parts of this book will cover the various methods for screening plaque.

Part 1 will list and compare the major methods for plaque measurement. Stress testing is the most common method, but even conservative standards bodies agree that it has major problems and is overused. We’ll cover 3 options that are better: coronary calcium score, CT angiogram, and CIMT. However, while these options are already available, far too few of us benefit from them. These aren’t used because they aren’t considered.

We will focus on the 2 major uses of plaque detection and measurement tests:

– Screening: checking healthy arteries to confirm or disprove the absence of plaque;

– Measurement and monitoring: documenting improvement or worsening plaque associated with interventions in lifestyle, supplements, medications, aging, and disease progression.

Good lifestyle choices are not easy to make. Even if we make good choices, it’s challenging to maintain them. Much of that is due to lack of awareness. If Russert had known he had inflammation, plaque rupture, and clot formation, would he have continued to delay dealing with his weight problem? He was quoted multiple times as saying “tomorrow” or “the right time.”

It was also reported that Russert had a positive calcium score (200) in 1998 (Lavie et al., Ochsner Journal, 2008). If that was true, why did he think “the right time” had not yet come? If he’d known that that meant a 10-year risk of 40% if untreated (Cafes de Cave), would he have thought it wasn’t time yet? It could have happened in the years between his positive calcium score and his death. We have access to testing that will inform us about arterial inflammation, yet we rarely use it.

I admit: CV inflammation is boring and a dry topic. However, that changes when we find out that we have plaque. When plaque is documented, the 10-year risk of a CV event jumps to 40% if left untreated. Unfortunately, most people don’t know that, either.

Part 2 will focus on a little-known type of screening and measurement called IMT (Intima Media Thickness). Out of all the options listed, it’s the only one that actually measures plaque without costing a lot, radiating you, or threading a tube through your groin and into your heart. This part will be less about the advantages and disadvantages. It will cover the scientific evidence behind this little-known test.

Part 1: How we currently measure plaque and why that’s hurting us

Plaque is critical. It’s the cause of heart attacks and strokes. Heart attack is the number 1 cause of death, while strokes are the number 1 cause of disability. Plaque is also implicated with Alzheimer’s disease, kidney failure, and blindness. It’s very common, like in 87% of 63-year-olds (Hakon et al., “Prevalence of Carotid Plaque in a 63- to 65- Year Old Norwegian Cohort From the General Population: The ACE 1950 Study”).

So:

1. How do we screen for plaque?

2. How do we measure plaque to monitor progress or regression due to lifestyle, treatments, disease, and aging?

There are lots of ways for screening major killers and disablers, like heart attack and stroke. Blood pressure screening, cholesterol screening, BMI screening, and others. Are these the best ways to screen for plaque? No. What is the most common way to screen for plaque? Isn’t it stress testing? Who doesn’t know someone that developed chest pain, went to the doc, got a stress test, then got a stent?

Stress tests

By far, the most commonly used medical test is the stress test. Over 5 million are done each year in the US alone. That’s unfortunate because stress tests aren’t effective for measuring plaque. As Russert’s story demonstrated, the stress test is not a great predictor of upcoming heart attack or stroke. Stress tests will only indicate that there is a plaque in the artery if there is more than 50% occlusion (blockage) of blood flow in the artery.

Unfortunately, 68% of heart attacks occur in people with less than 50% occlusion of flow. This brings up the first big problem with stress tests—false negative tests. Tim Russert’s test was a false negative. The second big problem with stress tests is false positives. False positive stress tests are one of the major reasons why patients are unnecessarily sent to the cath lab.

For almost a decade, the standards have not supported this much stress testing. The following guidelines have advised against exercise electrography in asymptomatic, low-risk individuals (Choosing Wisely®, “Annual EKGs for Low-risk Patients,” AAFP News, https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/cw-ekg.html):

– The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF, 2011)

– The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP, 2011)

– The American College of Cardiology (ACC) Foundation (2010)

– The American Heart Association (AHA) (2010)

Why? What’s the harm in checking? We saw the problem with false negatives in the Russert case. The new evidence we cited here was the damage associated with false positives—those usually go on to the cath lab for at least an angiography. Usually, that’s non-eventful. But not always.

Invasive Angiograms

The next common medical procedure done to measure plaque is a cardiac cath angiogram. That involves going into the cath lab, anesthetizing the patient, sticking a catheter into an artery (usually the large femoral artery in the groin), directing the catheter up through the aorta into the coronary arteries, injecting radiation dye into the coronary arteries, and taking a picture of the arteries using radiation detection equipment.

Obviously, this is not a screen for healthy people of any age. It’s not as highly dangerous as many people think. About 1 or 2 in a 100 result in a significant problem, and it’s usually bleeding from the femoral artery in the groin injection site. But then again, this procedure is still dangerous, uncomfortable, time-consuming, and expensive to be used in any situation other than significant known risk.

Here’s another problem: Over a million of these angiograms are done in the US alone. Most of them are due to finding something unusual on a stress test. So things get back to the problem with stress tests.

CT Angiograms

The CT angiogram is not highly utilized yet. But the science is indicating that it should be. The SCOT-HEART and PROMISE trials indicate that CT angiogram does a better job of predicting events and informing care than the standard stress test.

ABI (Ankle Brachial Index)

This is incredibly simple, cheap, and easy. It’s not very specific, but it’s worthwhile. All you need is a blood pressure cuff and a bed.

Calcium Score

The coronary calcium score is the next test we’ll discuss. It’s not that well-utilized yet. It doesn’t measure plaque. Instead, it measures calcium in plaque. Using CT technology, calcium is measured in the coronary arteries that supply the heart. The calcium scan is far better than a stress test or a cath lab angiogram, as it’s cheap and painless.

However, due to the significant radiation from the calcium scan, it’s best used with middle-aged people. Due to the radiation from the CT (computerized tomography) technology, calcium scores will never be done on healthy young people as a screen.

Another disadvantage is that calcium score measures calcium, not plaque. And yes, I’ve seen patients that actually had significant soft plaques in the coronary arteries, but very little calcium. That’s not common.

Another disadvantage is related to the fact that the calcium score doesn’t measure plaque—it’s not very good for monitoring progress. Only a few people will get a recommendation to undergo calcium scan more often than every 5 to 10 years. It’s just too difficult to use the data to measure progress (or the occasional decline) effectively.

Part 2: IMT

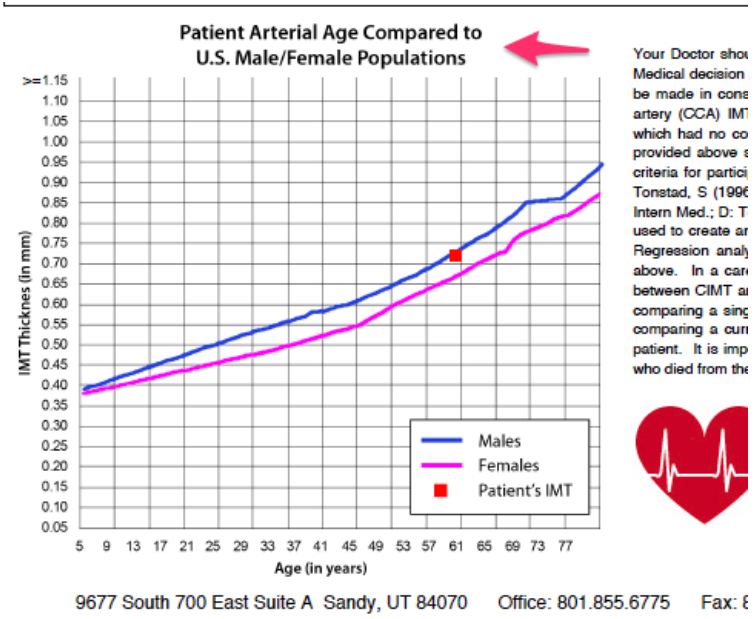

The Carotid Intima Media Thickness (CIMT) test is the only screening technology that’s effective for screening healthy people of all ages. It has been done enough to show nomogram curves (curves showing the average CIMT ratings of healthy people of all ages and both genders).

The typical nomograms (see below) for CIMT were developed using thousands of readings on healthy people of all ages. You won’t see this with any other method of screening. All other techniques are too invasive (invasive angiography), involve radiation (nuclear stress test, calcium score, CT angiography), expensive (invasive angiography, nuclear stress test), or unreliable (Ankle Brachial Index, all forms of stress test).

So, why don’t we see people lining up for IMT screening at your local or corporate health fair? There one key reason: it’s challenged with standardization and reliability of the technique. In fact, many would have included IMT in the “unreliable” category. We’ll examine that concern in this book. This process has clearly been done in research environments. That’s why the nomograms exist. We’ll also cover a lot of the key scientific evidence regarding IMT.

Radiation

We’ll mention radiation several times in this book. Here are some basics:

– There is no radiation at all with CIMT, ABI, stress (or exercise) EKG, or stress echo.

– There is radiation with calcium score, CT angiogram, nuclear stress test, and invasive angiogram, as well as stenting.

The calcium score has less than 1 mSv (millisievert, a measure of absorbed radiation by the body), so it’s not a practical concern for the typical 60-year-old looking for clarity about whether his heart attack risk is less than 5% or more than 40% over the next 10 years. However, unlike with CIMT, calcium score nomograms will not be done on healthy younger age groups. You just won’t see ethics review boards agree to calcium score testing of thousands of healthy young people, even though the potential radiation risk is relatively low.

We have to specifically mention radiation in stress test and invasive angiogram. Invasive angiogram and nuclear stress tests typically result in 2-10 mSv, while stents result in 15-20 mSv. Here’s where radiation becomes a real concern. There are patient/doctor combinations that occasionally result in a dozen repeats of various combinations of the following: nuclear stress test followed by invasive angiogram followed by stents. This practice in 40- and 50-year-old patients could become a significant radiation cancer risk.

Part 1

How We Currently Measure Plaque And Why That’s Hurting Us

Chapter 1

Stress Tests – How Not To Measure Plaque

I often tell the Tim Russert story at the beginning of my seminars. The purpose is to demonstrate that a lot of routine medical practices should be reexamined from the perspective of disease prevention. One time, when I was telling the story at an event in Florida, a hand shot up. I usually encourage discussion at my presentations, but this was just within the first five minutes of my talk. “Dr. Newman is my doc. And he’s my friend. He’s a very good doc…” These were comments, not questions.

As they continued, I listened, wondering whether we’d be able to regain control of the seminar. Surprisingly, it went very well. I explained that I still think Newman is a great doctor. He did a lot of good for public health. And Russert’s death was over 10 years ago now. The science has progressed. I’d do a few things differently for a similar case should I encounter one today.

Unfortunately, too many doctors don’t do anything differently. In fact, they would still recommend the stress test. Some doctors at least give some effort in educating patients that this test could cause more trouble than help. I have similar cases presented to me at all times, and so do a lot of doctors.

So even though your doctor will suggest a stress test, know that there are far better things to do. Patient-directed care is becoming more recognized and respected as the future of medicine.

What’s a stress test?

Other names for stress tests are stress EKG, exercise EKG, exercise electrocardiogram, and functional testing (as opposed to anatomical testing) of the coronary arteries. Also, be aware that there are multiple types of stress testing: nuclear, echo, and drug-induced. Each of these can have some variation in names, including stress EKG, stress echo, nuclear stress, and drug-induced stress test. MPI (myocardial perfusion imaging) is also another name. We’ll provide more details later.

The concept behind stress testing is a simple one. Is there a plaque blocking the arteries supplying the muscle of the heart? If so, it seems logical that stressing the heart muscle should demonstrate the problem. How would you tell if there is a relative lack of blood supply? There are a couple of indicators. First, there are symptoms, mostly chest pain. But there are other potential symptoms as well, like nausea or dizziness. Stress tests sometimes have to be terminated due to shortness of breath. In fact, any of the symptoms that can be seen with a heart attack can also be seen with a stress test.

The medical community has struggled for a long time with the issue of stress testing. It’s been known for over a decade that stress testing doesn’t find plaque. If it doesn’t find plaque, how could it ever be used to measure plaque? Maybe that’s okay because it predicts heart attack and stroke events, right? Well, that’s not clear, either.

What is clear is that stress tests don’t predict events very well. According to the Princeton Longevity Center, stress tests won’t pick up blockage of arteries (occlusion) until the blockage is greater than 50%. Yet, 68% of heart attacks occur in patients with less than 50% occlusion.

That’s why I’d love to see patients and doctors in the US divert 10% of the resources currently spent on stress testing toward IMT or even coronary calcium scans. It would make such a big difference in the prevention of heart attack and stroke.

The four types of stress tests

There are 4 basic types of stress tests: stress EKG (or ECG), stress echo, nuclear stress tests, and drug-induced stress tests. There are also other variations of imaging, such as the use of MRI technology (cardiovascular magnetic resonance) or SPECT scanning.

Drug-induced stress test

The idea behind stress testing is to measure the result of the heart’s reaction to stress. It’s looking at the dilation of the vessels. The drug-induced stress test uses drugs (dipyridamole or adenosine) to stress the heart and cause the arteries to dilate.

During exercise, the body generates energy, using a molecule called ATP (adenosine triphosphate) as the currency for energy. The “A” in ATP is a chemical called adenosine. This adenosine causes dilation of the arteries of the heart.

A drug-induced stress test bypasses exercise and causes the vessels to the heart muscle to dilate by directly infusing adenosine. That way, the heart’s reaction to stress can be measured even if the patient is

unable to walk, run, or cycle.

Stress EKG/Stress ECG

Stress EKG (or stress ECG ) is the original stress test. The idea again is to look at the response of the heart to stress; this time, it’s EKG or ECG. The patient walks for about 10 minutes on a treadmill. Including dressing, showering, and getting prepared, the full process will take about an hour. 4 records are generated: the amount of work as measured by speed and incline on the treadmill, the EKG or ECG, biometrics (like heart rate and blood pressure), and the patient’s record of symptoms (such as breathlessness, levels of fatigue, etc.).

Stress echo

The stress echo is the same as the stress EKG, except that it adds a cardiac echo before and after the stress events. The goal is to get the second echo reading within a minute of getting off the treadmill. Again, the total patient time, including preparation and dressing, is about an hour. The same 4 records are generated: work, symptoms, biometrics, and EKG. However, there is a 5th record: the echo reading in response to cardiac stress.

Nuclear stress test

The nuclear stress test is now, by far, the most popular type of stress test. Over 8 million nuclear stress tests are done each year in the US. It’s basically similar to stress EKG and stress echo. But instead of adding a cardiac echo, there is an addition of radioactive thallium tracers (radionuclide). It takes about 15 minutes to give an intravenous infusion of this tracer, and it can take a couple of hours to read the distribution of the tracer.

The typical time for a nuclear stress test is 3 to 4 hours. This time, the four records (work done, symptoms, biometrics, and EKG) are supplemented by the reading of the distribution of the radioactive thallium tracer.

Cost of stress tests

Doctors usually see stress testing as inexpensive. For the purposes of this book chapter, I checked a few websites. Here’s what I found:

– Choosingwisely.org: $175 or more.

– Mdsave.com: The national average is $891.

– Healthcarebluebook.com: $160 to $606 for fair price estimates.

– Abcnews.go.com: $200 for a basic stress test, with an average of $630 for nuclear stress tests.

– Health.costhelper.com: Patients with medical insurance covering a portion of the cost of the stress test procedure can expect to pay $200-$400 total out of their pockets, depending on the patients’ copay responsibility.

- Harvard Pilgrim Health Care: Members are charged $270-$379 for the test itself and an additional $24- $39 for an interpretation of the test. Uninsured patients will likely pay $1,000-$5,000 for a stress test and the analysis.

– Newchoicehealth.com: $4,400 national average, with a range of $1,200 up to $11,700.

Which stress test is the best?

Only around 10% of stress testing done are variants of the simple stress EKG. Majority of stress tests are stress echo, stress thallium, or other variations (stress using MRI, stress SPECT imaging, etc.). Despite being the cheapest, you see that stress EKG isn’t popular anymore. The reasons should be obvious. As seen with cases like Tim Russert’s, it’s clear that a stress EKG doesn’t accomplish much in terms of ensuring health.

Yet, over four million stress tests were done in the US last year. And this was stress testing for one reason alone—angina. This doesn’t include any of the millions of stress tests done for other purposes, such as failure or primary prevention.

From a cost perspective, take a look at the prices—they will range from as low as $200 to over $6,000. The lower numbers are for stress EKG; the higher numbers are for nuclear stress tests. Why is there a variation? When you look at these prices online, you will often not see each test’s specificity. Instead, you’ll see all the stress test procedures lumped together.

So if the stress EKG isn’t good, which of the others is?

There is an old quote I learned in medical school that goes something like this, “If there are multiple solutions for a single problem, it means that none of them works very well.” Concerning this quote, let me emphasize the critical truth about stress testing again: Stress tests do not pick up blockage until it’s over 50%, yet 68% of heart attacks occur in patients with less than 50% blockage (Princeton Longevity Center).

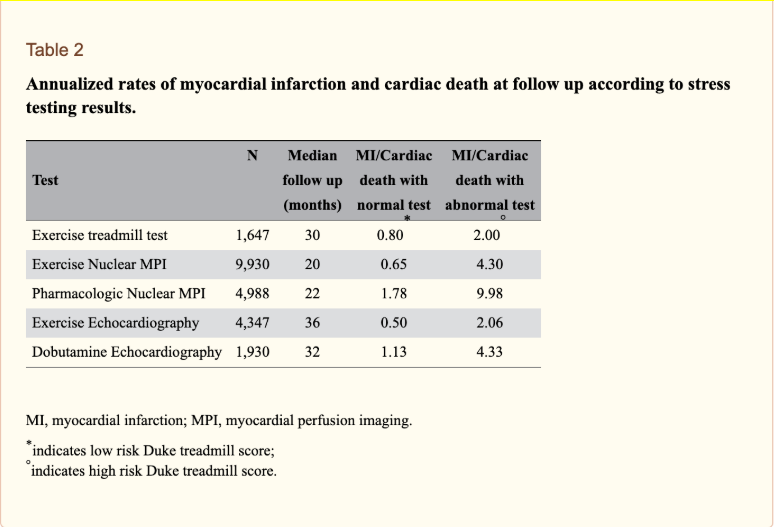

Sensitivity and specificity of the different types of stress tests

Both the sensitivity and specificity of nuclear and echo stress tests are better than that of the stress EKG. Most doctors will tell you that. But ask them what the sensitivity and specificity are. A meta-analysis (review of multiple studies on a specific topic) published in the Annals of Internal Medicine gave the following numbers:

– Exercise (or stress) EKG: 68% and 77 % in 132 studies of over 24,000 patients;

– Stress echo: 76% and 88% in 6 studies of 510 patients;

– Nuclear (thallium) stress test: 79% and 73% in 6 studies of 510 patients;

– SPECT rMPI: 88% and 77% in 10 studies of 1,174 patients;

– PET scan stress tests: 91% and 82% in 3 studies of 206 patients.

(Garber AM, Solomon NA. “Cost-effectiveness of alternative test strategies for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease.” Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999; 130(9):719.)

Here’s another way of looking at the stats.

(From Arbab-Zadeh. Heart International. 2012 Feb 3; 7(1): e2.)

Perhaps you’re thinking that those numbers aren’t that bad and that they don’t jive with the fact I gave earlier about most heart attacks occurring in patients with less than 50% occlusion. Rather than get into the technical and confusing definitions of sensitivity and specificity, I’ll go simply to the bottom line of the Garber study above.

In the first meta-analysis, there were only 7 days of difference in life expectancy based on the selection of the type of stress test—meaning, it made no difference. That obviously begs the question of whether doing any stress makes a difference in predicting life expectancy. The SCOT-HEART and PROMISE trials have recently shown that CT angiography is more reliable. Unfortunately, I know of no trials yet measuring this critical outcome for the other better options (CIMT and calcium scores).

So when your doctor recommends a stress test, ask him what type then ask him why. He’ll usually say nuclear stress test, then he’ll start talking about sensitivity and specificity. Ask him if he can define the sensitivity and specificity in stress testing that he’s using to support his recommendation. Very few can. In fact, most can’t define sensitivity and specificity in general. Believe it or not, this is not a criticism of your doctor. It’s a criticism of our medical standards process.

Dilemmas: Logical, therapeutic, financial, and ethical

So why are so many stress tests still being done? Remember that stress tests only pick up >50% occlusion, yet most heart attacks occur in patients with less than 50% occlusion. That’s it. That should be game over for stress testing.

But if you’re a doctor, what do you say to those patients coming through your door? They’re sitting in your waiting room. They’re waiting to tell you that their uncle just had a fatal heart attack, and they want to make sure they don’t have a problem. They’ve thought about it (well, they’ve certainly worried about it a lot). It seems to them that if they can pass a stress test, that’s the best assurance possible that they don’t have a plaque problem. Sadly, they haven’t really heard (or read) that much about this issue.

This is similar to the recurring problem with antibiotics for colds. Many patients assume that the treatment or test (like antibiotics or stress tests) will bring them relief. And if they don’t, at least they tried. There is also the assumption that if the antibiotics or stress tests don’t work, there is no harm done. That assumption may be correct but too often wrong.

Patients, doctors, and financial/ethical dilemmas

Here’s the reality. Patients have expectations, and doctors will attempt to meet those expectations. For many doctors, it’s just the financial concern of losing patients. They went into medicine with a desire to help people, and that translates into wanting to keep their patients happy.

Many doctors will say that things are not as simple as what I’m saying here. For example, there is some predictive value in stress tests, particularly for patients that get to very high levels of exercise. Plus the fact that some populations are high-risk while others are low-risk further complicates this issue.

There are also financial realities. Stress test revenue is at least significant for many doctors. It is easy to criticize this point, but criticism based on ethics can be difficult in an environment with widespread violations and lack of clarity. Stress tests are incredibly common, actual indications (or reasons given for doing them) are myriad, and even labeling the procedures isn’t simple.

False positive stress test

There are a lot of symptoms that can be interpreted as a false positive stress test, ranging from breathing hard to chest discomfort. By definition, symptoms are subjective in nature.

But it’s not just symptoms. The classic stress EKG looks for changes on an EKG. The classic signs are changes in the ST segment. There could also be abnormal heartbeats or rhythm. Blood pressure can go either high or low enough to call an end to the test. Stress echo looks for changes in the shape and structure of the heart based on ultrasonic (echo) images. Nuclear stress tests look for the distribution of the radioactive tracer.

Certain medications can impact stress test results as well. For example, beta blockers are often given for heart failure or even just high blood pressure. Beta blockers keep the heart rate from increasing. That’s obviously a big deal for a test stressing the heart’s response to exercise.

What if you’re healthy and low in risk, but you just want to confirm that you do not have any problems? Would a screening stress test be a good idea? Wouldn’t it be good just to document current capacity and lack of any unknown problems?

False positive stress tests lead to cardiac caths which, in turn, lead to stents

Stents have a very similar backstory with stress tests. About 2 million stents are done each year in the US. However, many standards bodies—from ACC and AHA to internal and family medicine groups—agree that stents are overutilized. To these groups, too many stress tests and stenting are being done.

In the right situation, stents can save lives. But the right situation (post-heart attack) only occurs at less than 200,000 times per year. So what about the other 1,800,000? They’re done for two reasons:

– Prevent heart attacks. Unfortunately, that doesn’t work. The most well-known trial showing this fact is the COURAGE Trial. This was mentioned by Dr. Newman in the NBC News Special Report on Tim Russert’s death.

– To cure angina. That doesn’t work either, as shown by the ORBITA Trial (published in The Lancet in 2018).

The COURAGE Trial was published in The New England Journal of Medicine way back in 2007. It demonstrated that stents “did not reduce the risk of death, myocardial infarction, or other major cardiovascular events when added to optimal medical therapy.” Moreover, the ORBITA Trial showed that stents “did not increase exercise time by more than the effect of a placebo procedure.”

This ORBITA Trial was an interesting study. Why? It was done in five centers in the UK. Researchers actually randomized the subjects to a sham procedure. In other words, all patients went through pre-op and were even anesthetized for a stent. But the study group did NOT get the stent; they just got a “sham” procedure. And, yes, they did just as well as the ones that went through the complete actual stent.

It’s hard to imagine patients in the US agreeing to be anesthetized for a sham procedure, even if the investigators could get things funded. But at this point, it’s hard to imagine anyone debating that that’s not important enough for the cost and risk to the patients. This is an indication that we’re routinely putting millions more at greater risk for no predictable benefit.

These are just two studies, but other studies don’t contradict the evidence shown by the COURAGE and ORBITA Trials. That’s why groups like the ACC (American College of Cardiology) have teamed with Choosing Wisely®, an affiliate of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. To get an idea of all the situations in which the ACC has discouraged continued stents, just go to the site, and search for PCI (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention).

On the part of Choosing Wisely®, the organization stated on its website that its mission is “to promote conversations between clinicians and patients by helping patients choose care that is:

– Supported by the evidence

– Not duplicative of other tests or procedures already received

– Free from harm

– Truly necessary

In 2012, national organizations representing medical specialists started asking their members to identify tests or procedures commonly used in their field, whose necessity should be questioned and discussed. This call to action has resulted in specialty-specific Lists of “Things Providers and Patients Should Question.” (Choosing Wisely®, Our Mission, https://www.choosingwisely.org/our-mission)

Overutilization of stress tests and stents

So why do patients still continue to get stress tests and stents? What do doctors tell their patients that come in with plaque and its associated fear? What do they do when both parties agree to a stress test, and then the stress test shows abnormalities? Well, what else can they do but go straight to the cath lab. And once in the cath lab, what else can they do when they see plaque other than putting a stent.

Again, stress tests and stents overutilization is similar to overutilization of antibiotics and stem cells. There is a huge vacuum in an area of great need. Without antibiotics, there won’t be a cure for the common cold. Without stem cell, there won’t be a cure for most arthritis, stroke, or dementia. Without stress tests and stents, there will be insufficient knowledge of appropriate screening methods for arterial plaque. And there will be a shortage in good ways of measuring and following the progress (or regression) of plaque.

As you can see, patients and doctors are somehow pushed to create answers to this need. So they come up with an “obvious” answer. But the obvious answer here—stress testing—is not good. Too many false positives lead to the cath lab and getting stents.

But false positive stress tests are often not as bad as false negative stress tests. Tim Russert’s false negative stress test gave him hope that his exercise was making up for his poor diet. That was a false sense of security with a lethal outcome. How often is that same scenario being repeated today with the same lethal consequences?

Since there is a major lack of appreciation among physicians and patients for the better screening tools (CIMT, calcium score, and CT angiograms), the result is the overuse of the obvious one—stress test. This problem of serious illness and supposed lack of solutions lead to financial and ethical dilemmas. It’s a trap for medical overuse.

Stents and the overutilization formula

Here’s the overutilization formula. First, there’s a serious illness. Second, there is a logically obvious treatment. Third, unfortunately, the logical “cure” doesn’t really work. It may make a lot of sense, but it just doesn’t work. So, the logical dilemma (that the obvious treatment doesn’t work) leads to therapeutic, financial, and ethical dilemmas.

Let’s fill this in for stents. First, having lots of plaque in your coronary arteries is undoubtedly a serious condition. Obviously, the real danger is a heart attack. I hope this fact is not too repetitive, but half of heart attacks are immediately lethal. So for stents, the first criterion (“there’s a serious illness”) is certainly met.

How about the next criterion (“there is a logically obvious treatment”)? Of course, if you’re plumbing has a block, ream it out. That’s pretty obvious to most patients and doctors. So stents meet the first and second criteria.

On the third criterion, here’s where you may argue with me. Most people know at least someone that has had immediate and lasting relief from a stent. Doesn’t that prove the logic that stents actually work? Going back to the COURAGE and ORBITA Trials, we’ve been shown that this obvious treatment—stents—may not really work.

Strokes and the overutilization formula

Stenting is not the only situation in modern medicine where overutilization occurs. Another example is stroke. First of all, strokes are serious. 1 in 4 events will result to death immediately. The other 3 are likely to disable permanently, putting victims in wheelchairs or nursing homes for decades.

The second criterion is that there is an obvious treatment that fits well—carotid endarterectomy. It is a surgery to remove plaque from the arteries of the neck suspected of being the major source of stroke.

As for the third condition, there was a slight twist. Carotid endarterectomy doesn’t work in smaller centers. That’s because the higher the volume of this type of surgery in the hospital, the safer the surgery will be. This is not unusual. Higher volume centers are safer for most procedures.

So if the medical marketplace were behaving based on the benefit of the patient, then low-volume facilities would have 1 of 2 choices. The first choice—to become high-volume centers—is beyond unlikely. There were just too few people in their communities with plaque in their carotids. The second choice is to send their few cases to the higher-volume, larger centers. Neither happened. There was actually a slight decline in the number of operations.

One of my surgical attending physicians in medical school was the high-volume carotid endarterectomy provider for our area (lowland South Carolina). His name is Max Rittenbury. He was known for having a fiery, uber-efficient personality. And he had a significant risk factor for plaque himself—he was morbidly obese.

I remember him calling me down for reading my surgery text one day in 1983 in one of our discussion sessions. Technically, he had the right to do so. But that was my own incorrect way of practicing my own problem with the situation. I didn’t like him. I could never see good surgeons in the smaller towns giving up their livelihoods, especially to a man like him. I also couldn’t see patients having to travel so far or their families having to go to accompany them, all for the privilege of having to put up with the Blue Max. Obviously, I wasn’t the only one that felt that way.

There was actually a decrease in carotid endarterectomies in the low-volume centers. But even during the low point of the decline, the rates were “persistently two to three times as high as that in Ontario throughout (this) period” (“The Fall & Rise of Carotid Endarterectomy in the US & Canada,” New England Journal of Medicine, Nov 12, 1998).

Healthcare costs and the overutilization formula

The US fails to control surgical and medical procedure utilization. You don’t have to be a doctor or a medical economist to know that. Atul Gawande, MD, moved this discussion forward 10 years ago, starting with his article “The Cost Conundrum” (The New Yorker, May 25, 2009). He didn’t say that all doctors practice medicine for financial gain; just a lot of them, and that is driving healthcare costs.

We studied that almost 30 years earlier, in 1983, in my health policy management classes at Hopkins. In those 30 years, things had not improved; they got worse. Now, it’s been another 10 years since Gawande’s The New Yorker article, and it’s still not getting better. In fact, it’s getting worse.

But this was more than a rant about runaway healthcare costs. If the US is going to manage healthcare cost utilization, we are going to have to be willing to put patients and family through travel and surgery in the hands of a difficult, untrusted surgeon.

Gawande was correct. Physicians are driving healthcare costs. I’ve made a career of supervising physicians, and there is a theme to that type of experience. The theme is that physicians are people too. In other words, it’s like plumbers and mechanics. It’s far too easy to find things wrong and advise expensive fixes. But unlike plumbers and mechanics, these “fixes” often don’t work. So instead of just wasting money, the patients go through the risk of added medical procedures and still end up with dubious “improvement” of their original situation.

So how do we manage over-utilization?

Leaving the insurance companies in charge of utilization management has not been a popular option. Insurance companies have proven to have their own challenges in the area of managing over-utilization.

Another option is the government provision of healthcare. That creates another set of problems. This is beginning to sound like the quote from Winston Churchill, “Democracy is the absolute worst form of government, except for all others.” No matter what your political leanings, healthcare over-utilization is still a major problem. It occurs every time there is a medical problem without a good solution. The obvious—but incorrect—solution becomes over-utilized.

False negative stress test: Back to the Russert story

Remember the Tim Russert story in the “Introduction”? His stress test was most likely a false negative. As Carl Lavie mentioned in a subsequent Ochsner Revue analysis, “Given that he had a negative stress test, the LAD (Left Anterior Descending) probably never occluded over 50%.”

That’s the biggest danger of stress testing: getting a negative test. You don’t realize that there is the likelihood of getting a false negative. You’re thinking you’re healthy, and there’s much less risk than you feared. You breathe a sigh of relief. You relax your diet, weight loss, and other activities. You go back to Dunkin Donuts for breakfast. (I’m not implying that Russert ate doughnuts. But it was clear to all that Dr. Newman was correct in using this as an opportunity to warn the public of the dangers of obesity.)

Whether the patient was Tim Russert or you, the stress test was negative because you didn’t have a 50% occlusion. It may be 30%, but you were currently in a metabolic mode of laying down plaque. Your immune system is doing what it could to clean out this plaque—it was attacking the plaque.

What happened at the cellular level?

Monocytes were diving through the glycocalyx and into the oxLDL that had been deposited in the intima-media space. These monocytes were becoming active. They were growing. They were joining other activated monocytes, forming foam cells. And they were releasing their enzymes (Lp-PLA2) that they used to destroy and digest cellular trash.

Other types of immune cells called polymorphs or neutrophils are arriving to contribute to the action as well. They’re doing the same thing as monocytes. The increased plaque and inflammatory activity are attracting them to the artery walls where the plaque is being deposited. The neutrophils are releasing their own enzyme (myeloperoxidase or MPO).

At the time of Russert’s death, his doctor, Dr. Newman, was well-respected and continued to be respected. His knowledge, concern, and attention to detail were demonstrated through the investigation of the case. He went beyond the standards of care by getting the CRP (C-reactive protein). Even today, ten years later, that’s beyond the standard of care. Unfortunately, CRP can vary too much. It also has too many false positives. That’s why I recommend getting a complete panel, which includes MPO, LP-PLA2, and MACR.

I haven’t seen any mention of MACR (microalbumin creatinine ratio) for Russert’s case, but I’d be surprised if Dr. Newman had not gotten it. MACR is often done within standard medical circles. Given the quality that Newman demonstrated, he probably did get it. It was probably elevated. And Russert probably didn’t understand the danger it portended.

My verdict on stress tests and stents

Management of plaque is beyond the scope of this book. However, I will make a few comments about how to manage and how not to manage plaque. I have to draw this comparison. The most common method for measuring plaque—stress testing—is the worst method. Likewise, the most common method of managing plaque—stents—is also the worst one.

Stents work well for treatment of heart attacks, but the treatment of heart attacks makes up only 10% of stent placements. The rest are for prevention of heart attacks and cure angina. It has been shown for over a decade that stents don’t prevent heart attacks (COURAGE Trial, The New England Journal of Medicine, April 2007). We’ve also known for a couple of years that stents really don’t seem to work in curing angina (ORBITA Trial, The Lancet, Jan 2018).

Lonnie’s stress test story

“I was born in New York. I’m 41 now. About 15 years ago, I was playing basketball and had these funny feelings in my chest. I went to the ER. Soon after that, I was getting a stress test. I’ve had them every year since then. I don’t really know what they’re trying to find.

It’s ok with me, though. Because I still worry about these flutters in my chest. I’ve had them with the annual treadmill tests. And a few cardiology consults. And a couple of Holter monitor tests. They tell me I have Paroxysmal Supraventricular Contractions. They say they’re like aberrant or off-track beats. They also say they’re fine, and that you just occasionally see these, especially in young, healthy men that work out a lot.”

Lonnie is a 41-year-old guy that’s in great shape. He doesn’t have a medical need for stress tests.