It’s important to screen and measure coronary plaque. And there are many ways to do it.

There’s the stress test that is used 5 million times a year. But it doesn’t always work. You have to have over 50% occlusion to detect plaque.

There’s the standard angiography. About a million people per year are tested this way, but it’s never going to be a great screening tool for an asymptomatic 30-year-old.

There’s the calcium score. It’s inexpensive. It’s easily accessible. But it’s not 100% good—it doesn’t quantify very well, and it uses radiation.

There’s also CT angiography. There have been some excellent studies (like SCOT-HEART & PROMISE) that prove the power of this technique. The price, though, is expensive.

All the above tests attempt to look at plaque in the arteries of the heart. That’s not surprising, as mostly the focus in medical practice is to measure the plaques in such locations. That makes sense. Plaque is the major cause of heart attack, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and other chronic conditions.

However, plaque doesn’t happen in a single artery. It’s systemic. If we can have it in one spot, then we can have it everywhere.

What is Peripheral Plaque?

This brings us to peripheral plaque. “Peripheral” refers to the outside of the heart area. Peripheral plaque is the kind of plaque in the arteries in the legs and feet.

Why look for peripheral plaque?

As I mentioned earlier, plaque is not localized. It happens not only in the arteries around the heart. It can form throughout the body.

What is PAD?

Another reason to look for peripheral plaque is that it can reduce blood flow to the limbs. This leads to a condition called PAD (peripheral artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, or peripheral vascular disease).

PAD affects over 13% of populations who are above 50 years (Crawford, 2016). It can cause pain while walking and may predispose PAD sufferers to heart attack and stroke. Among the factors that can increase the risk of PAD include diabetes, age, smoking, abnormal pulses in the lower legs, high lipid levels, and known presence of plaque

Now that we know what PAD is, how do we diagnose PAD? This is where the ABI test comes in.

What is the ABI Test?

ABI or the ankle-brachial index is a simple test that compares the arm (brachial) blood pressure to the ankle blood pressure.

From Physiopedia:

The ankle-brachial index, ankle-arm index, ankle-arm ratio, or the Winsor Index (first described in 1950 by Winsor) is a quick, non-invasive, inexpensive technique used widely to check the peripheral arterial disease (PAD). It assesses the severity of arterial insufficiency of arterial narrowing during walking.

ABI and Presence of Plaque

Blood pressure in the ankle is normally higher than blood pressure in the arm (Aboyans, 2012). If there is a lot of plaque in the blood vessels between the heart and the ankle, blood pressure is decreased in that area, which leads to an insufficient blood supply in the lower extremities. And this reduced blood flow is the characteristic of PAD.

Uses of the ABI Test

Pain in the legs while walking is a symptom of PAD, but not everyone with PAD will have symptoms. That makes testing important. The great thing about ABI is that it’s specific and quite sensitive in diagnosing PAD.

The doctor may also recommend the ABI test to check how well blood flows into the leg after surgery.

ABI can also be useful in assessing a person’s risk of heart attack or stroke.

The ABI is a measure of the severity of atherosclerosis in the legs but is also an independent indicator of the risk of subsequent atherothrombotic events elsewhere in the vascular system. The ABI may be used as a risk marker both in the general population free of clinical CVD (cardiovascular disease) and in patients with established CVD. (Aboyans, 2012)

How to Perform the ABI Test

The ABI test involves a hand-held Doppler or ultrasound device that’s pressed on the skin. During the test, you will lie on your back. Your blood pressure in the arms and ankles will be measured with an inflatable cuff (the same cuff used in the clinic). The blood pressure values will then be used to calculate ABI.

You can perform ABI by yourself with a DIY set-up. I’ve done this myself. All you need is an automated blood pressure monitor (like an Omron) and cuffs. Here’s how:

- Lie on the bed. Stay there for 5 minutes.

- Measure your arm blood pressure. Make at least 3 measurements. Get the average systolic blood pressure (SBP).

- Measure your ankle blood pressure. Make at least 3 measurements. Get the average systolic blood pressure (SBP).

- Calculate ABI by dividing your ankle blood pressure over your arm blood pressure.

For an illustration of ABI calculation:

- Here are my ankle blood pressures: 128/65, 127/66, and 130/70.

- Here are my arm blood pressures: 117/69, 115/53, and 110/62.

- We’ll be only using the SBPs: 128, 127, and 130 for the ankle; 117, 115, and 110 for the arm.

- Get the averages: 128 for the ankle; 114 for the arm.

- Get the ratio: 128 ÷ 114 = 1.1. This is my ABI.

How to Interpret the ABI Test

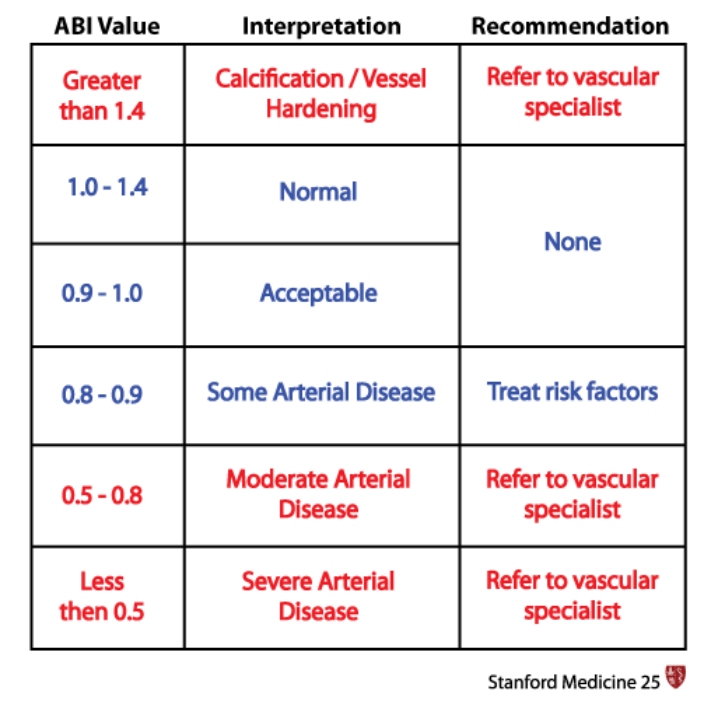

Here’s a nifty ABI guide from Stanford Medicine 25:

Normal ABI ranges from 1.0-1.4… Pressure is normally higher in the ankle than the arm.

Values above 1.4 suggest a noncompressible calcified vessel.

A value below 0.9 is considered diagnostic of PAD.

Values less than 0.5 suggests severe PAD.

Table of ABI values. Source: Stanford Medicine 25. Measuring and Understanding the Ankle Brachial Index (ABI).

How does my ABI fare? 1.1 falls in the normal range. It’s unlikely then that I have significant PAD.

High ABI vs. Low ABI

ABI and Cardiovascular Risks

From the table in the previous section, know that ABI values less than 0.9 indicate PAD. But a low ABI is not limited to PAD alone; it may also indicate cardiovascular risk factors and prevalent diseases.

From Aboyans (2012):

…A low ABI is associated with many cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking history, and several novel cardiovascular risk factors (eg, C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, homocysteine, and chronic kidney disease).

Is it safe to say that a higher ABI is better? Not at all. In fact, a very high ABI is also worth looking into.

From Aboyans (2012):

Few studies have evaluated the association of an abnormally high ABI, indicative of vascular calcification, with cardiovascular risk factors or with prevalent CVD (cardiovascular disease).

…High ABI is associated directly with male sex, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension but is inversely associated with smoking and hyperlipidemia.

…ABI >1.40 to be associated with stroke and congestive heart failure but not with myocardial infarction or angina.

High ABI and Risk of Amputation

There is also a study that shows people with very advanced disease can actually get paradoxically high leg pressures; hence, a very high ABI. Because of calcification, arteries going down to the lower extremities become so stiff that SBP can swing into high values. This is a risk factor for impending amputation (Silvestro, 2006).

For clarification, the paradoxical effect of overly high blood pressure is caused by dropping pressure, a mechanism that’s different from the mechanism which governs the more common plaque effect (which I discussed in the section “How Does ABI Show Presence of Plaque?”).

Let me elaborate: Blood pressure can be decreased by blockage of blood flow, but it can be raised as well. If it’s mostly blockage, there will be a decrease in pressure. If there is a minimal blockage but more rigidity of the artery wall, there can be an increase in pressure.

This is one of ABI’s major problems—The impact of plaque can actually drive the pressure in either direction. As you might guess, there could be a mix of these effects, masking the problem very well.

My Case

The confusion with ABI interpretation can sometimes be clarified through logic and context regarding the patient’s exercise capacity.

Take my case as an example. I have a normal ABI, so that could mean I don’t have PAD.

I’m also not worried at all about impending amputation. How do I know that? In my high-intensity interval sessions, I run up a slight incline at a 6-minute mile pace. No one at risk of amputation can do that kind of exercise. So I have pretty clear evidence from my DIY ABI test and my exercise pattern that I’m not at risk for amputation.

On the other hand, I do have evidence of plaque based on my CIMT and calcium score. My ABI findings simply show that this plaque is not at that extent to affect my blood flow to my legs.

Why is the ABI Unpopular?

ABI has a poor reputation for several reasons:

One, there’s the paradoxical blood pressure increase I described in the above section.

Two, there’s currently a lack of standards for measuring and calculating the ABI.

…the estimated prevalence of PAD may vary substantially according to the mode of ABI calculation. In a review of 100 randomly selected reports using the ABI, multiple variations in technique were identified… (Aboyans, 2012)

Three, resting ABI is not very sensitive. That means there can be a significant amount of plaque, yet there’s no impact on pressures. Therefore, the ABI often misses detecting the presence of plaque.

There have been trials of exercise preparation to improve ABI sensitivity (Montgomery, 1998). Although some investigators felt exercise could overcome this lack of sensitivity, the evidence has not been compelling enough to create a change in widespread medical practice.

Is It Safe to Take the ABI Test?

For most people, there are no risks. However, the ABI test is not recommended if the patient has a blood clot in the leg. If there’s a pain in the legs, a different test should be done.

If you found this article helpful and want to start taking steps toward reversing your chronic disease, Dr. Brewer and the PrevMed staff are currently accepting patients for a limited time. Book an appointment here: https://prevmedhealth.com/

To ensure the quality of care, limited openings are available, so act quickly.

References

Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Abraham P, Allison MA, et al. Measurement and interpretation of the ankle-brachial index: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012 Dec 11;126(24):2890-909. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318276fbcb.

Brewer F. Coronary Calcium Score: Under-Utilized But Still A Great Test. PrevMed website. https://prevmedhealth.com/coronary-calcium-score-under-utilized-but-still-a-great-test. Accessed December 31, 2020.

Brewer F. CT Angiography: The Plaque Screening Test with Lots of Potential. PrevMed website. https://prevmedhealth.com/ct-angiography-the-plaque-screening-test-with-lots-of-potential. Accessed January 6, 2021.

Brewer F. How Does Inflammation Cause Cardiovascular Disease? PrevMed website. https://prevmedhealth.com/cardiovascular-inflammation-and-plaque-formation. Accessed December 31, 2020.

Brewer F. How to Reverse 20 Years of Arterial Plaque. PrevMed website. https://prevmedhealth.com/how-to-reverse-arterial-plaque. Accessed January 13, 2021.

Brewer F. Reducing Arterial Plaque – Is It Possible? PrevMed website. https://prevmedhealth.com/reducing-arterial-plaque-is-it-possible. Accessed December 31, 2020.

Brewer F. Stress Tests, Cardiac Cath & Stents: The “Unnecessary” Triad. PrevMed website. https://prevmedhealth.com/stress-tests-cardiac-cath-stents-the-unnecessary-triad. Accessed December 31, 2020.

Brewer F. What a Stress Test Can (and Can’t) Tell You. PrevMed website. https://prevmedhealth.com/what-a-stress-test-can-and-cant-tell-you. Accessed December 31, 2020.

Crawford F, Welch K, Andras A, Chappell FM. Ankle brachial index for the diagnosis of lower limb peripheral arterial disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Sep 14;9(9):CD010680. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010680.pub2.

Johns Hopkins Medicine. Ankle Brachial Index Test. Johns Hopkins Medicine website. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/ankle-brachial-index-test. Accessed January 6, 2021.

Montgomery PS, Gardner AW. The clinical utility of a six-minute walk test in peripheral arterial occlusive disease patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998 Jun;46(6):706-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb03804.x.

Physiopedia. Ankle-Brachial Index. Physiopedia website. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Ankle-Brachial_Index. Accessed January 6, 2021.

Silvestro A, Diehm N, Savolainen H, Do DD, et al. Falsely high ankle-brachial index predicts major amputation in critical limb ischemia. Vasc Med. 2006 May;11(2):69-74. doi: 10.1191/1358863x06vm678oa.

Stanford Medicine 25. Measuring and Understanding the Ankle Brachial Index (ABI). Stanford Medicine 25 website. https://stanfordmedicine25.stanford.edu/the25/ankle-brachial-index.html. Accessed December 23, 2020.